The Missing “Crown”

Matityahu Friedman was a young journalist who came from Canada and began his career as a journalist with the international news agencies AP and ‘Jerusalem Report.’ In the course of his work, he covered events in Israel and the Middle East. One day, he heard about one of the most important books in the world, “The Most Precious Book of the Jewish People,” hidden deep within the ‘Shrine of the Book’ at the Israel Museum. His curiosity was piqued, and he decided to write an article about the book.

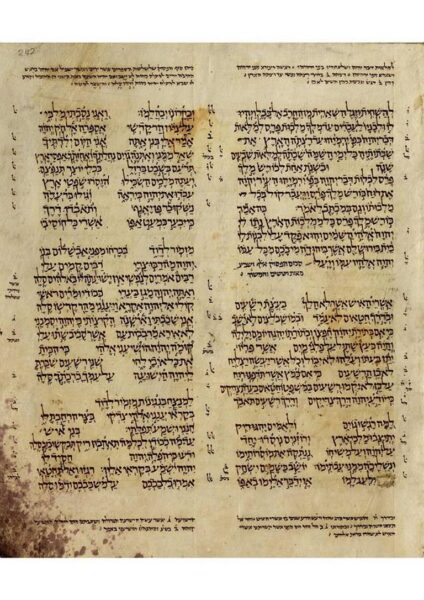

The most important book of the Jewish people is, of course, the Torah (Tanakh). The most significant version of this book is presumably the one written by Moses and passed down to the people of Israel, but it has been lost and is no longer available. However, how close can one get to that book written by our ancestors? The answer: the Aleppo Codex, a Bible written over a thousand years ago in Tiberias, Israel, which was determined by the great eagle, The Rambam, as the most accurate and precise version of the Bible.

Friedman went to visit the Israel Museum, entered the Shrine of the Book, and descended into the air-conditioned and dimly lit underground chamber where the Codex lay after a thousand years, written beautifully in ink on parchment. “There,” he said, “some pages of the Codex rest, only a part of the book. The other part, as I learned, lies deep in the museum’s vaults, preserved under tight security. But even this isn’t the entire Codex, as a significant portion of it – about two hundred out of its 487 pages – is missing.”

The missing Codex we have today starts with the phrase “And the rest” from the passage of curses in the book of Deuteronomy, chapter 28, verse 17, and ends with the word “Zion” in Shir Hashirim. That’s it. That’s all that survived. But Friedman was moved by the story of the Codex. He was deeply moved by what exists and what remains of it, and he decided to write about it.

Preservation Under a Thousand Eyes

The Aleppo Codex was written by the scribe Shlomo Ben Buya’a in ink on parchment, in the tenth century. The book was written as the foundational text, the correct copy, as per tradition, passed down orally from person to person until the event at Mount Sinai and as a guide during the exile, directing the writing of all Torah scrolls for eternity. Hence, it was written as a bound book, not in scroll form, making it easier to flip through without the effort involved in handling parchment scrolls.

After the precise lettering by the scribe, it reached the hands of the meticulous scholar and tradition bearer Aharon Ben Asher, who added vowel marks, accents, and tradition notations, and also corrected the lettering based on the tradition’s notes. Therefore, the book is accompanied by many annotations according to the tradition.

After a hundred years, the book was acquired by Karaite Jews and made its way to the center of the Karaites in Jerusalem, from where it began its wanderings. It was plundered by the Crusaders and offered for sale at a high price, eventually bought by the affluent Jewish community of Egypt for an enormous sum of money.”

And so, that’s how the Aleppo Codex came into the possession of The Rambam, who testified about it, ‘Everyone relied on it because Ben Asher meticulously corrected and checked it many times, as they transcribed it, and I relied on it for the Torah scroll I wrote according to its rulings.’

Years later, turmoil began in Cairo, and after the ‘Codex’ found itself in Egypt, David ben Joshua, the grandson of The Rambam, took it to Syria. He brought the Codex to the city of Aleppo, known as a city and mother in Israel, abundant with scholars and scribes. The Jews of Aleppo, who understood the value of the ancient book, were deeply moved by its arrival. In the city’s central synagogue, called Aram Tzova, there were seven chambers, the most important of which was Eliyahu Hanavi’s Chamber,’ where the book was kept as a precious treasure. On the opening page of the book, it was inscribed: ‘Holy to God, shall not be sold nor redeemed for eternity. Blessed be the one who guards it, and cursed be the one who steals it.’ The community believed their fate was tied to the fate of this precious Codex. Year after year, century after century, the precious Codex was preserved and its value increased in the eyes of the community. It was so precious that they locked it within multiple safes, one within another, a box within a box, locked with multiple locks, with the keys held by two community leaders who never allowed anyone to see it. It couldn’t be opened without the presence of two leaders of the community. The community believed that their fate was tied to the fate of the Codex, and as long as it remained intact, they felt secure.

Seemingly, they were right. The Codex was guarded meticulously, and the fact that no one touched it allowed the thousand-year-old book to survive under the vigilant watch of the community and the synagogue officials. The book was so well-preserved that when researchers tried to study it, they were refused. In the 1930s, researcher Moshe David Cassuto traveled to Aleppo to request permission to photograph the Codex, but his attempts were futile. Rarely did the community agree to allow anyone to examine the Codex, and when they did, it was under strict supervision. Cassuto had to comply. He spent a week in Aleppo, examining and making notes on the Codex, but that was the closest anyone could get to it.

“According to testimonies,” Friedman narrates, “they told in Aleppo that if the book were to be removed from its place, even if it were just shifted, calamity would befall the community, a plague or a great disaster. They said that once, when the book was moved, an epidemic broke out, which ceased only when the book was returned to the synagogue. And even those who don’t believe in miraculous books,” he points out, “see the facts that indeed, since the Codex left the community of Aleppo, the community has perished.”

Loss & Turmoil in Aleppo

In the year 1947, with the UN’s partition decision and the establishment of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel, severe riots broke out against the Jews of Aram Tzova. Arab marauders targeted Jewish homes and synagogues, and mobs invaded the Jewish quarter, ravaging, looting, and setting fire to many houses and most of the synagogues. The British Consul in Halab reported firsthand that “groups of rioters attacked Jewish institutions, houses, and shops. The police and the army did nothing, and some policemen even participated in the looting. The disturbances continued all day, and it was only the next day that the governor sent forces to restore order and protect Jewish property.”

The rioters particularly targeted Torah scrolls, taking forty of them from the synagogues and burning them. For two days, the Jews remained confined to their homes until they dared to venture out. When they did, they first rushed to the synagogue to ascertain what happened to the Crown (the Torah Crown). However, their searches amid the smoldering ruins of the ancient synagogue did not yield anything. The Ark was shattered, and there was no sign of the Crown. It was evident that it had burned along with the other Torah scrolls. The Crown, preserved for a thousand years, did not survive the Muslim riots. When news of its demise spread, the entire Jewish world mourned. The oldest book of the Jewish people was no more. Kasuto wrote an article lamenting the lost Crown.

But they were mistaken. In fact, the Crown or part of it survived miraculously. Recently, Avi Dabach, one of the synagogue attendants and a shamash, created a program aired on Channel ‘Kan’ that unveiled the story of the Crown. The last guardian and shamash of the synagogue was Asher Begaddi. His daughter, Carmela, who was interviewed for the program, recounted her memories of that dreadful night when her father was urgently called to save the treasury in the synagogue. “There were shouts, ‘Asher! The synagogue is burning!'” she recounts. “There were shouts, ‘Palestine is our land, and the Jews are our dogs.’ Then they shouted to call my father. My father went and saw that the synagogue was on fire. After a few hours, he arrived and saw that the Crown’s ark was shattered, and its pages were scattered everywhere. My father took a sack and collected all the pages, some partially burnt and torn, some completely burnt in a corner. Then marauders came and tried to attack us. There was a large, robust Arab to whom I pleaded to save us, and he stood against the rioters and told them, ‘These are not Zionists. These are our neighbors. Go attack the Zionists, not our Jews.’ He expelled them, and we were saved.” The book was saved and hidden by one of the community’s rabbis, keeping it concealed. The community found it convenient for everyone to believe that the entire book had burned, as it prevented the authorities from searching for it.

Finally, in the 1950s, under pressure from the second President of Israel, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, the remnants of the Crown that survived the fire and theft were smuggled to the State of Israel when it was incomplete and damaged. It was transferred to the Israel Museum and has since been preserved in the “Shrine of the Book.”

This, at least, was the official version.

In a washing machine on the way to Israel

“What an emotional story it was,” says Friedman, “How the book that survived a thousand years, like the Jewish people, burned in riots, and its remnants returned home to Jerusalem after so many years.”

Friedman wrote the article at the time, which was published in the newspaper he worked for, but he soon discovers that almost nothing he wrote about the last cycles of the book is accurate.

Friedman began to dig and discovered layer after layer of what actually happened to the book. He wanted to know precisely how it survived, who transferred it, and how, but encountered locked doors and evasions. He also discovered to his astonishment a detail that was carefully concealed: the book made it complete to Israel, or almost complete.

But first, the initial detail: In fact, President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi was a book-loving person who dreamed of bringing the book to Israel and to the institute he established. Even before the establishment of the state, he initiated the mission of the community leader, Yitzhak Shmush, to bring it from Halab (Aleppo) to rescue the book. Shmush, who knew the Halabi legend that when the book leaves Halab, destruction will come to the city, knew the odds were slim. Still, he pleaded with the Halab community council to allow the transfer of the book to Israel. However, after stormy debates, it was decided that the book would not be moved from its place.

His friends, concerned that the book’s place in Halab was unsafe, opposed the decision and offered him a peculiar suggestion. “You’ll give us the number of your safe deposit box on the train, and you’ll take with you, instead of your personal suitcase, a large empty suitcase. We’ll bring you the book, its place is in Jerusalem.” Shmush reacted, “I won’t bring it by theft.” When he returned, he faced Ben-Zvi and told him the story. Ben-Zvi, who later served as president, was less enthusiastic and responded, “Pity we didn’t send a straight man.”

Year after year, a hundred years and another hundred, the precious book was preserved, and its value increased in the eyes of the community members. It was so valuable that it was locked in a chest within a chest, a box within a box, a lock on top of a lock, with the keys to the locks held by the heads of the community.

“Did he initiate bringing the crown to Israel? No, not at all. In a document exposed by Avi Dvahach, a Mossad agent named Yonah Cohen excitedly informed Ben-Zvi that the crown survived. ‘I was given personal information,’ the Mossad agent relayed, ‘that the crown is in the hands of the community.’ He further added that the community leaders who stood against the transfer of the crown to Israel were no longer around. The agent hoped to somehow bring the crown to Israel, but failed.

Ben-Zvi made an emotional appeal to the immigrants from Halab to assist him in bringing the crown to a safer place in Israel, but his efforts went in vain.

A decade passed since the establishment of the State of Israel, and the situation in Syria worsened. Members of the Halabi community began fleeing, and in 1958, two rabbis, Rabbi Moshe Twil and Rabbi Shlomo Zafarni, decided that it was time to move the crown to a safer location. They turned to their trusted man, Mordechai Ben Ezra Pacham, a resident of the city who was a cheese merchant and had Iranian connections and received a deportation order from Syria. Before leaving the city, the rabbis secretly asked him to take the precious book and smuggle it to Israel. He was instructed to hand it to the community leader, Rabbi Yitzhak Dayan, who had escaped to Tel Aviv.

The Chacham family hid the book inside an old washing machine. ‘I found a piece of white fabric,’ recounted Serena Pacham, Mordechai’s wife. ‘I placed the crown inside, tied it, and put it inside the washing machine. I put grains, onions, clothes, and such on top. That was it.’ The machine, holding the precious treasure, was loaded onto a ship leaving Syria, and there, Pacham met a representative of the Agency who discovered that he was holding the coveted crown and reported it to the operatives in Israel.

Meanwhile, the Pacham family arrived in Haifa and settled there. According to their statements and others’, the crown remained intact despite all the upheavals. This was also testified by one of the community’s scholars, Rabbi Yitzhak Schwikha, who saw the book before it was sent to Israel while it was still hidden in a warehouse. ‘The book was intact,’ he said, ‘only a few pages were missing from the beginning, from the Book of Genesis.’

Upon Pacham’s arrival in Haifa, he was warmly received by one of the Agency’s men, Shlomo Zalman Shragai. Shragai, who served as the first mayor of Jerusalem after the establishment of the state for two and a half years, was a Jewish traditionalist and a Mizrahi leader. Impressed by his appearance, Pacham decided to entrust the crown to him. According to Shragai’s son’s testimony, even when the book was in his father’s possession, it remained intact, except for a few missing pages from the Book of Genesis. However, he did not enjoy the treasure for long. President Ben-Zvi was informed that Shragai had the crown and he sent policemen to confiscate it from him. Since then, the book has been housed at the Ben-Zvi Institute under the supervision of its director, Professor Meir Benyahu.

A Mystery

Where did the missing pages disappear to? Here’s something else that remained hidden for years: the rabbis from Halab arrived in Jerusalem after all their sufferings, and to their astonishment, the book somehow ended up at the Yad Ben Zvi Institute, not with Rabbi Dayan, who was the initial destination for the book’s shipment. They sued the state and demanded the book’s return. Fridman uncovered the court proceedings. ‘If Rabbi Dayan wasn’t in Israel,’ Rabbi Moshe Twil stated in court, ‘we wouldn’t have sent the crown at all.’ But Pacham argued that he was instructed to hand the book to a religious Jew, and when he found out that Shragai was a religious man, he delivered the book to him.

Fridman doubts Pacham’s version, ‘It’s more logical that the rabbis told him to give it to someone from their community, not to a stranger.’ It’s unclear what happened to Pacham on the way and what, perhaps, he negotiated with the agency representative he met. The court ruled in their favor, but ultimately, the state refused to comply, and the book remained under a compromise agreement in the state’s possession.

As often happens, once the book reaches its destination, people lose interest. The book was stored in one of the institute’s cellars, abandoned and nearly forgotten. For almost thirty years, the ‘crown’ sat in the Ben Zvi Institute’s storage in a regular office cabinet, wrapped in cloth. Neglect caused damage to this precious manuscript, rendering parts of it illegible. A report from the 1970s described it shockingly: ‘The Aram Tzova crown is locked in a regular office cabinet…(wrapped in cloth)…Today there are places in the manuscript that are unreadable compared to a few years ago.’

After several years, it was decided to transfer the crown to the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum for preservation. While some parts could be restored, the missing pages could not be recovered. Thus, over the years, it was revealed that parts of the crown went missing, and no one knew why or how.

At this point, Rafi Siton, a member of the Halabi community and a clandestine Mossad agent, entered the picture. He had seen the crown with his own eyes in his hometown of Aleppo and, after learning about the crown’s fate, decided to dedicate himself to uncovering the matter. As Siton revealed, ‘My father went and saw that the synagogue was on fire. After a few hours, he returned and saw that the crown’s box was broken, and its pages were scattered everywhere. My father took a sack and collected all the pages, some of which were burnt, into the sack.’

After the transfer of the Crown to the Yad Ben Zvi Institute, a portion of the book went missing. Shragai himself, in a letter sent to the president of the Hebrew University, expressed significant concerns about the potential public scandal if the event were to be revealed. When exposed to Professor Esses from the Yad Ben Zvi Institute about the missing portions of the book, he requested police involvement, yet this plea was rejected by Ben Zvi.

The Yad Ben Zvi Institute holds a different version regarding the missing parts. They claim that the book arrived to them already lacking a central part. Rabbi Yitzhak Shachiber, who was the last to see the book in its entirety, testified that a quarter of it was missing. However, Sitoon claims to have heard from Rabbi Shachiber that the book was complete, missing only a few pages from the beginning.

Sitoon suggests that Ben Zvi could be involved, yet due to the necessity for an in-depth examination, he refrains from making definitive statements, which weakens his claims. The Yad Ben Zvi Institute’s stance refutes this, maintaining that the book arrived to them lacking a part from the beginning.

Later on, Sitoon accuses Ben Zvi, but the Yad Ben Zvi Institute denies it, still asserting that the book arrived to them with parts missing from the beginning.

Hints, investigations, and mysteries unfolded over the years, with various attempts made to solve the puzzle of the missing pages. The mission was to locate the missing manuscripts, estimated to be worth tens of millions of dollars. Alongside Sitoon, Ezra Ktzin, also of Halabi descent, Professor Yossi Ofer from Bar-Ilan University who researched the Crown, Dr. Raphael Zar from the Hebrew University, an expert in biblical manuscripts including the Crown, and the journalist Yifat Arlich, were enlisted.

The latest testimony regarding the whereabouts of parts of the Crown came from the renowned antiquities dealer Shlomo Musayof. He recounted in a testimony documented by Sitoon: “Two men came to me, two elderly Jews with sidelocks, wearing big black hats, asking if I was Mr. Musayof. I said ‘yes,’ and they told me, ‘We have something very important to show you.’ I went with them to a room, they placed a suitcase on the bed, opened a silk cloth covering it, and suddenly my eyes widened. I saw between 70 to 100 pages, one placed on top of the other, written on parchment, with black ink that had faded over time. One line slightly shorter, the next a bit longer. They told me it was the Aram Zova Crown.” Sitoon presented Musayof with a fax of the Crown, and after inspecting it, Musayof confirmed, “Yes, this is it. I have no doubt that what I saw was the Crown.”

But the price demanded by the traders was too high, and Musayof did not purchase the Crown. Later, Musayof revealed that the mentioned trader was the late Rabbi Chaim Sneiblag, a well-known Judaica dealer, who was found lifeless in a hotel room in Jerusalem some time after. While his death was speculated to be a murder, the circumstances remained obscure. As for the Crown, if it was in his possession, it disappeared from his authority without a trace.

The frustration among scholars and biblical researchers is immense, given that there isn’t even a photograph of the missing sections, and there’s no way to recover them for future generations. However, Musayof’s testimony gave Sitoon hope. Since then, Sitoon has been convinced that remnants of the Crown exist somewhere, held by someone, and all that remains is to find them.

Meanwhile, the mystery of the Crown has generated countless speculations. According to one claim, those who took the Crown are members of the Halabi community in the United States, who consider the Crown their property and a sacred amulet protecting them from harm. This was potentially supported by an incident in 1982 when a woman from Brooklyn submitted a page from the Crown’s manuscript to the National Library without explaining how it came into her possession. However, another section that reached the Ben-Zvi Institute hinted at a different direction: a small excerpt containing verses from the Book of Exodus, donated by the family of Shmuel Sebag. Sebag reportedly lifted the fragment from the floor of a synagogue in Halab just after a disturbance. He held the piece in his wallet as an amulet until his death in Brooklyn some years ago, when the family decided to move it to Israel.

Dvach, who was committed to the investigation, also traveled to the United States, leveraging his family connections and familiarity with the community to try and determine if, and where, the Crown’s pages might be located. Unfortunately, no further information was uncovered. Some researchers believe that the truth may never be revealed without the establishment of a state inquiry committee to gather testimonies and thoroughly investigate what happened to the manuscript. However, Dvach doubts the likelihood of a truth-revealing inquiry committee. “An inquiry committee could also bury things. As we’ve seen in the case of the Yemenite children, there were one or two inquiry committees, and nothing was revealed. It might be the same in our case, perhaps even more so.”

It seems that the new presentations and information gathered from the public provide new directions and reinforcements to the investigation. But there isn’t a definitive breakthrough yet. Dvach remains determined to continue searching for the missing parts, understanding the stubbornness of the Halevi community in preserving the Crown for so many years. Will the mystery of the Crown finally be unraveled? It’s still unclear, but as information and research progress, there’s hope that we are now called to uncover the depths of the mystery and find the absolute truth.